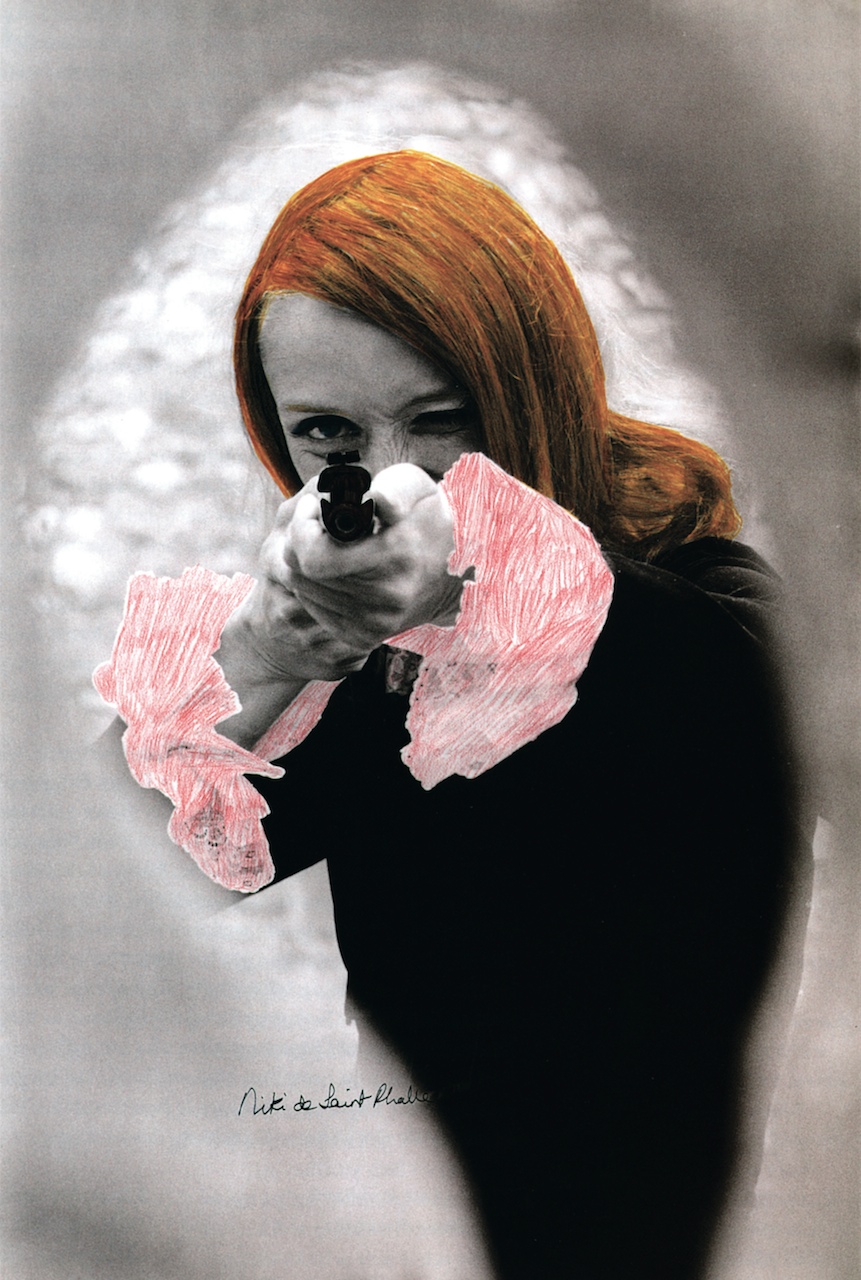

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Autoportrait” (“Self-Portrait”) (c. 1958–59) (© 2014 Niki Charitable Art Foundation; all rights reserved; photo by Laurent Condominas)

PARIS — Niki de Saint Phalle was half French, half American, and bilingual, but who was she? Certainly not merely the sculptor who made those fat girls, the Nanas, though they remain her most famous works. The greatest surprise of her retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris is how different those works look alongside the rest of her creations, and how strikingly varied yet coherent her large body of work is.

Camille Morineau, the show’s curator, is best known for her startling exhibition at the Centre Pompidou five years ago, elles@centrepompidou, for which she rehung the museum’s permanent collection with only women artists. Now she dazzles us with this thorough exploration of de Saint Phalle’s unfettered imagination.

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Heads of State (Study for King Kong)” (spring 1963) (© BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Michael Herling/Benedikt Werner)

The show opens with collages and paintings in earnest dialogue with Pollock, Dubuffet, and Rauschenberg that the self-taught artist made between the ages of 28 and 31. From 1960 to 1963 she executed her famous Tirs (Shoot) pieces, which drip like Pollocks but which de Saint Phalle produced by shooting a rifle at balloons of colorful paint mounted on white canvases. In the early 1960s, this aristocratic Catholic woman who’d been brought up in a strict household attacked the church with sculptures in the shape of altars strewn with crucifixes. In the mid-‘60s she constructed giant, heavy-hearted bride-ghosts and modern Venus of Willendorfs squeezing out babies. In perfectly calibrated formal choices, de Saint Phalle disfigured long-held articles of faith — high art, the family, the church.

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Les Trois Grâces” (“The Three Graces”) (1995–2003) (photo by Veronique Bidinger) (click to enlarge)

But then, seemingly out of nowhere, came the Nanas, those girls as heart-stoppingly different from de Saint Phalle’s previous work as Cézanne’s “The Eternal Feminine” is from any of his still lifes or Mondrian’s grids are from his early writhing trees. These Nanas — rotund, ebullient, hungry girls dressed in bold primary colors — twirl on tippy toes and look like they’re having a grand old time. They glance back at French art history to Matisse’s jubilant dancers and the sturdy females of Gaston Lachaise and Aristide Maillol, and even, surprisingly, to Rodin.

The Nanas’ forms may be French, but their attitudes are American. Think Stuart Davis, Red Grooms, Roy Lichtenstein, comic strips, and gumball machines. They seem to say: break all the rules, be confident, be arrogant, and throw your weight around. De Saint Phalle makes her audience enter “Hon” (1966), a house-sized Nana, through her vagina.

There’s another side to the story, though. In 1968, de Saint Phalle wrote on a drawing, “I had to take my diet pills … gained five pounds around the hips.” On another drawing of a Nana she asks, “will you still love me when I look like this?” The artist was a slim woman who modeled for Life magazine when she was 19, Vogue when she was 22. Following a conventional trajectory, she married at 19, had her first child at 21, and her second at 25. At 23 she had a nervous breakdown and was treated with electroshock therapy and insulin for what was diagnosed as schizophrenia.

When she was 62 de Saint Phalle published Mon Secret. She revealed that her father sexually abused her for several years beginning when she was 11 years old. Knowing this, all her works take on new meanings and what seemed like contradictory urges — the guns, the sad and sullen wives and mothers, the enormous, rollicking Nanas — take their places in a cohesive narrative. The raging critiques of the early works transform into the reveling forms of the fat Nanas, and later into de Saint Phalle’s jubilant, sometimes macabre parks all over the world. Their size and colors resemble a kind of voodoo against malevolent spirits.

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Cheval et la Mariée” (“Horse and the Bride”) (1964) (© BPK, Berlin, dist. Rmn-Grand Palais/Michael Herling/Aline Gwose)

De Saint Phalle’s work is close to the American feminist artists of the ‘70s and ‘80s, especially Anita Steckel, Carolee Schneemann, Joan Semmel, Joyce Kozloff, and Miriam Schapiro. Her discourse in newly uncovered film clips from 1965 featured at the Grand Palais is entirely consistent with contemporaneous American feminism — direct, acerbic, critical, and demanding. Between 1942 and 1944 Saint Phalle went to the Brearley School, a girls’ prep school in New York. It was there, she said later, “[that] I became a feminist. They inculcated in us that women can and must accomplish great things.” However, there was no feminist art movement in France in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Without a women’s community and the writing and curatorial practices that were produced by it, de Saint Phalle never got the sure footing in France she might have found in the US.

The Grand Palais show belatedly gives her the platform she lacked in her lifetime. The exhibition sprawls across 21,500 square feet and is organized neither chronologically nor thematically. Morineau complicates viewers’ narrow, Nanas-focused vision of de Saint Phalle and contextualizes those works within the artist’s other passions. She begins by enticing visitors with unexpectedly confident and little-known early works in a gallery that leads up to giant precursors of the Nanas. A crescendo builds from that first space to an even larger one crowded with Nanas everywhere: huge, painted, covered in mosaics of mirror and colored glass, with some sculptures standing on the ground and other, inflatable Nanas climbing up a wall and onto the ceiling. On the exhibition’s lower level, the violence of the Tirs paintings troubles the exuberance of the Nanas. The exhibition’s final galleries feature fanciful elements from her vast garden projects alongside vivid video evocations of walking in these outdoor environments. Throughout the exhibition, in intimate corners and passages between larger spaces, video interviews, Life and Vogue magazine covers, documentary photographs, and walls of frolicking figure drawings with speech bubbles of witty and biting commentary provide more biographical background and contextual material for the big, bold works on view nearby.

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Tea Party, or the Tea at Angelina’s” (1971) (photo by Mike Marron)

Despite the exhibition’s aesthetic power and intellectual rigor, no major Anglophone newspaper or magazine has published a serious piece about it, and it is not scheduled to travel to any English-speaking countries. One wonders why the Anglo-American art world is so uninterested. Is the work too upbeat, too much fun, too decorative? Too feminine? It worked out so much better for that other French-American artist, Louise Bourgeois, whose work by contrast is so dark and serious, so modernist and masculine.

If ever there was a chance to see the irrepressible de Saint Phalle in all her glory, this show at the Grand Palais (and, soon, the Guggenheim Bilbao) is it. She once said, “I always admired people who went all out.” As this exhibition makes abundantly clear, she did just that.

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Dolorès”

(1966–95) (© 2014 Niki Charitable Art Foundation, All rights reserved)

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Leto ou La Crucifixion” (“Leto or the Crucifixion”) (1965) (© Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Georges Meguerditchian)

Niki de Saint Phalle, “La Mort du Patriarche” (“The Death of the Patriarch”) (1972) (© 2014 Niki Charitable Art Foundation; all rights reserved; photo by Laurent Condominas)

Peter Whiteread, “Niki de Saint Phalle en train de viser” (“Niki de Saint Phalle Taking Aim”) (1972) (© Peter Whitehead)

Niki de Saint Phalle continues at the Grand Palais (3 avenue du Général Eisenhower, Paris) through February 2. It will run February 27–June 11 at the Guggenheim Bilbao.